On an October night in 1913, Czech poet Hans Janowitz was walking through Hamburg's notorious Reeperbahn, looking for a girl "whose beauty and manner attracted him." He followed her laugh into an adjacent park, where she vanished into the shrubbery with a man. The laugh abruptly stopped. Unnerved, Janowitz hung around and finally saw the shadow of a man emerge, his face like an "average bourgeois" as he passed. The headlines next morning read "Horrible sex crime on the Holstenwall!" Janowitz attended the girl's funeral, convinced that he had witnessed the crime; and there he locked eyes again with the "average bourgeois," who seemed to recognize him.

This incident served as the inspiration for Janowitz's script, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, albeit abstracted through the prism of a shattered Imperialist Germany. It wouldn't be an overstatement to say that German film starts with 1919's Caligari, and while the term "Expressionism" is often applied loosely to all films from the period, Caligari is one of a handful that plays by the aesthetic rules of that movement, with its jagged set design, chiaroscuro lighting, and stilted, arrhythmic performances. The cinematic German Expressionists (the movement was already underway in drama and art) were not concerned with what they considered mundane reflections on nature or the recording of simple facts. It wasn't destruction, death and totalitarianism they wanted to expose but the interior visions these things provoke, filtered through the senses and refracted back as a more accurate representation of human experience. Mind giving form to matter, not the other way around -- the driving creative force of the writers and set designers.

But mind giving form to money was preferable to the producers. They brought in director Fritz Lang to help make the surreal story more palatable (and exportable) but, due to other commitments, he had to drop out of the project early on. Despite his short tenure, Lang's one recommendation infuriated the writers by bookending the narrative with "lunatic asylum" segments that they felt undermined the script's anti-authoritarian message. Thus, the murderous, sleepwalking "everyman" manipulated and controlled by the totalitarian master became a deus ex machina by a guy in a straight jacket. Both the producers and new-director Robert Weine loved the idea and felt it would give Caligari more international appeal, putting the upstart German film industry on the map.

Other events helped to do that. And after Hitler and what the West perceived as the complete acquiescence of the German citizenry to Nazi will, the film's subtext was so undeniably clear that the framing device hardly mattered anymore. Instead of the first classic horror film, Caligari became a huge unheeded warning cry that things were still amiss in the collective German psyche, that the servant /master game was still brewing behind the scenes in the Weimar Republic, or so thought expatriates like Siegfried Kracauer, whose 1947 study From Caligari To Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film set the scholarly debate framework for decades to come, until feminist film theory began to challenge some of those sacrosanct ideas. The film's reputation continued to grow. Over the decades, it became an art house perennial, the iconic image of somnambulist Conrad Veidt (later the lead Nazi in Casablanca) cropping up on album covers, advertisements, and t-shirts. Of all the Weimar era films, only Lang's Metropolis can claim such a lasting impact on our popular culture.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

On March 10, 1925, Otto Rothstock, a 25-year old dental technician, entered the publishing offices of writer and social activist Hugo Bettauer. As a curious Bettauer watched on, Rothstock calmly locked the door behind him, turned to face the desk, and fired a revolver five times into Bettauer's chest at point-blank range. Such was the harmonious union between politics and art in Germany's Weimar Republic.

Okay, in all fairness, Austria. Bettauer was a well-known and publicly-despised left wing journalist and author who had managed to carve out some notoriety for himself via his scathing exposes of the Viennese bourgeoisie, his weekly publication credited with at least one corrupt official's suicide. He called for legalizing abortions, advocated for married women to retain their maiden names, and railed against existing sexual mores, which he criticized as pious, patriarchal, and out of step with the new spirit of modernity. Rothstock was a budding proto-Nazi, convinced that his impromptu assassination and subsequent surrender (he hung out on the office sofa and waited for the police to arrive) was a public service in the grand name of Austrian nationalism, to rid the state of at least one fly in its ointment. Bettaeur lingered on for a week or so. Rothstock was deemed "insane" and back on the street in 18 months. A small-yet-prescient window into the future.

Although popular in his day and publishing 3-4 novels per year, Bettauer's literary legacy (if one could call it that, given his almost complete obscurity) rests on two works, both of which were serialized in Austrian newspapers. His most famous, Die Stadt ohne Juden from 1922, or City Without Jews, gained more of a reputation after the war, when it was reassessed as an ominous harbinger of things to come (the use of freight cars strikes a particularly eerie parallel.) In Bettauer's alternate reality, however, the Viennese citizenry expel all Jews from the city only to realize that, without them, their capital is crumbling and culturally deficient, at which point the mayor welcomes them all back with open arms and much public pageantry. The fact that the author uses this mass expulsion as a comically-improbable extreme to heighten the novel's satiric impact only reflects the pre-1933 limits many Europeans placed on state-sponsored antisemitism.

But oddly, it was Bettauer's 1924 Die freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street) that got him killed: an indictment of the corrupt Viennese establishment dressed up as a murder mystery. Like "crime" writer Horace McCoy's They Shoot Horses Don't They? or the blacklisted Guy Endore's Werewolf of Paris, Bettauer used the "penny-dreadful" genre as a vehicle to communicate broader universal truths to the masses, to pose uncomfortable questions and shed light on hypocrisies and social inequities. And purportedly, it was this that director and fellow Austrian G.W. Pabst saw in Bettauer's novel as well.

For his film adaptation, Pabst ditches some of the novel's more melodramatic elements and puts the transient presence of the "street" front and center, a dark and claustrophobic artery tenuously linking its disparate inhabitants. Pabst's love of Bertolt Brecht is in evidence, with lives alternately shaped and destroyed by poverty and opportunity, struggles for simple sustenance juxtaposed with a crass, opulent hedonism. Greta Garbo gets her big non-Swedish break here, quickly snatched up by Hollywood shortly after the film's release and hitting it big internationally. Even more impressive is the performance of screen veteran Asta Nielsen, who comes across as hauntingly ethereal in scenes, part mousy librarian, part powdered drag queen. Werner Krauss, who plays the notorious butcher, is better known for being the sadistic doctor in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. His only requirement of Pabst was that his dog get good screen time as well. The sacrifices you make I guess.

Very few of the silent films now considered masterpieces of the German Weimar era have the difficult history of The Joyless Street. Granted, it was not uncommon for international silent films to suffer at the hands of foreign editors. With no sound synchronization to worry about, editors and projectionists could (and did) butcher at will, deleting entire sections, rewriting intertitle cards between shots, or whatever was needed to "sanitize" a film and get it past local censors. In a couple of snips, brothels became orphanages and prostitutes became volunteers for the Salvation Army (to cite two German examples, the latter from another Pabst film). The relative completeness of its German counterparts—Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, Der Golem—reflects the fact that, much like today, horror is tolerated better than sex in the U.S. market, particularly in the 1920s when cinema was still a burgeoning industry and hypersensitive to any critiques of its morality. So a cheery Teutonic rumination on starvation, sexual degradation, and economic collapse was sure to bring the x-acto knives out in force. Almost immediately, 150 minutes became anywhere from 120 to 90 to 57. Some reviewers of the day could not even piece together the basic narrative. A second obstacle faced by the restorers was the lack of any existing intertitles in the original German. For the purposes of this restoration, Filmarchiv Austria painstakingly recreated these using a combination of a 1926 censorship report, an early draft of the shooting script, and foreign print intertitles retranslated back into German.

The result: as close to Pabst's finished vision as we will ever see, and an incredible restoration achievement that was over ten years in the making.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

“Sex was the business of the town. Inside my Berlin hotel, the cafe bar was lined with the higher-priced trollops. The economy girls walked the streets outside. On the corner stood the girls in boots, advertising flagellation. Actors' agents pimped for the ladies in luxury apartments in the Bavarian Quarter. Race-track touts at the Hoppegarten arranged orgies for groups of sportsmen. The nightclub Eldorado displayed an enticing line of homosexuals dressed as women. At the Maly, there was a choice of feminine or collar-and-tie lesbians. Collective lust roared unashamed at the theater. Just as Wedekind says, 'They rage there as in a menagerie when the meat appears at the cage.'"

-- Louise Brooks, "Pabst & Lulu."

______________________________________________________________________

Like Gray Gardens, Eat the Document, and Superstar: the Karen Carpenter Story, Mädchen in Uniform is one of those rare films whose only availability in the pre-Internet days came through the grainy bootleg copies that film buffs passed around hand to hand. The bad VHS copy I saw in college had the English subtitles partially truncated at the bottom, with Japanese subs taking up 1/3 of the right (couldn't get this copy for our screening purposes unfortunately.) Art transmitted through those types of personalized, underground channels always takes on some contraband aesthetic that inevitably influences ones interpretation of the work itself; so within the early-90s college film community, Mädchen in Uniform quickly became known as "that German lesbian movie banned by Nazis that they were watching in Henry & June." I believe this deep scholarly analysis should be expounded upon.

Looking back on the film's critical readings, one sees an interesting shift through the decades. In 1931, while the underlying homosexual overtones were noted and commented upon, this was not seen as a particularly important aspect of the story, at least with regard to media attention. Perhaps this had much to do with context, given the over-the-top sexual liberation of Weimar Berlin, where a suppressed love affair between headmaster and pupil would have been quite quaint compared to Marlene Dietrich's raunchy performance in The Blue Angel, the film that took the LGBT subculture in Berlin by storm, according to Hertha Thiele. Hence, until the 1960s, scholarship and critical reception focused almost exclusively on the film's indictment of Prussian militarism and its dehumanizing and destructive influence upon German society, which was by far a greater concern among the nation's cultural cognoscenti. Thiele says that this was also the narrative angle emphasized by Froelich, despite his later collaboration with the Nazi Party.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

“Sex was the business of the town. Inside my Berlin hotel, the cafe bar was lined with the higher-priced trollops. The economy girls walked the streets outside. On the corner stood the girls in boots, advertising flagellation. Actors' agents pimped for the ladies in luxury apartments in the Bavarian Quarter. Race-track touts at the Hoppegarten arranged orgies for groups of sportsmen. The nightclub Eldorado displayed an enticing line of homosexuals dressed as women. At the Maly, there was a choice of feminine or collar-and-tie lesbians. Collective lust roared unashamed at the theater. Just as Wedekind says, 'They rage there as in a menagerie when the meat appears at the cage.'"

-- Louise Brooks, "Pabst & Lulu."

Of all the Weimar films, it is perhaps Pandora's Box that has undergone the biggest reassessment by film scholars over the past sixty years, going from a much maligned failure upon its 1929 release to one of G.W. Pabst's essential masterworks today. Much of that has less to do with Pabst than with the enduring and mysterious legacy of its major star, Louise Brooks, an American actor not particularly adept at sticking to the expected playbook of the Hollywood studio heads. One quick read through any of her acerbic New Yorker essays from later in her life provide plenty of points for possible collision between Brooks and the old-boy studio network. Many women could no doubt navigate it with clenched smiles and gritted teeth, but Kansas-born Brooks, always ready to speak her mind, was not among them. When she got the call from Pabst to come to Berlin, she had little to lose and few bridges left to burn. German film scholar Lotte Eisner tells the story of showing up on the set and seeing Brooks sitting in a chair between takes, reading a book that she assumed to be American pop culture fluff or dime-store romance. Haughtily confronting her, Eisner was embarrassed and shocked to see it was Schopenhauer's Essays in translation. In her later classic work on Weimar film The Haunted Screen, it was Brooks, not Pabst, that Eisner praised as a genius.

Eisner's initial hostility should be seen in context. Even before casting was finished, German literati attacked the idea of a base film (film was perceived as inferior to stage and still a novelty at best) derived from Frank Wedekind's two dramas, Erdgeist and Die Büchse der Pandora, which the film synthesizes into a single narrative. Incorporating elements later adopted by stage Expressionists, Wedekind's dialogue-driven dramas were highly controversial for their candid, if highly stylized, assault on pious sexual attitudes of the late 19th-century. And when, during the high-profile casting search, German actresses like Marlene Dietrich were passed over for an American, it was the final insult. Berlin reviews were brutal and the film failed miserably.

Problems on the set are legendary. Brooks spoke no German and had to be coached phonetically on all her lines (silent film viewers were excellent lip readers and often complained when lip movements failed to match the dialogue text.) Pabst could only communicate with her in broken English. Alice Roberts, unhappy about playing one of the screen's first lesbians, requested that Pabst speak seductive French to her from offstage so she could make it through her tango scene with Brooks with her moral universe intact. The veteran actors didn't hide their hatred of the lead, calling Brooks the "spoiled American" brought in to portray "their beloved German Lulu." Instead of diffusing these onset tensions, Pabst often worked, in his quiet and erudite manner, to exacerbate them, knowing this would only heighten the intensity of the performances. The tactic, however ethically questionable, worked to perfection. Brooks said she had the bruises on her arms to prove it after several physical scenes.

Today, Brooks's naturalistic performance and iconic look, with her laissez-faire disposition, black bob and bangs, has come to personify the post-WWI "Jazz Age" mentality, the embodiment of joie de vivre and sexual liberation. In Pandora's Box, the fact that this impulse leads to the ugly inverse says more about masculine paranoia over the erosion of traditional power balances than the emergence of any feminist ideals. Perhaps it is that disorienting dichotomy--championing the new in one fist while reinforcing the old with the other--that strikes such a continued chord with viewers, as the film gets reinterpreted through the filters of media theory.

Strangely, despite their large age gap, both Pabst and Brooks were at the ends of their careers. Pabst made two incredible sound films--Westfront 1918 (1930) and Kameradschaft (1931)--before fading into obscurity with second-rate costume dramas during the Nazi years, which was thankfully the extent of his collaboration. Brooks was blacklisted after she refused to return to Hollywood and convert her silent performance in The Canary Murder Case into a sound version, another actress ultimately dubbing in her lines. The ensuing smear campaign that her voice did not translate well into sound sealed her fate in the industry. She taught dance lessons for a while before becoming a recluse in her Rochester apartment, only leaving to replenish her library book supply. She wrote extensively during this period and had many articles published in The New Yorker and various film journals, later assembled into the well-received book Lulu in Hollywood. It was Henri Langlois and the exploding French film community of the 1960s that brought Brooks to a new generation, with a big retrospective at the Cinematheque Francaise, to which she was invited and treated as royalty by the younger New Wave filmmakers of the day.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

One has to wonder what actually succeeded among German moviegoers during the 1920s, since most of the films now lauded as classics were so maligned in their day. Amazingly, given its accessibility and continued fame nearly a century on, F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror falls into that sad category. It was the first effort by the newly-formed Prana-Film, one of the first "indies" that attempted to compete with the state-sponsored Universum Film AG, or UFA, which enjoyed a virtual monopoly in German film production. But an unexpected intervention by outside parties ensured that Prana-Film's first release would also be its last.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

One has to wonder what actually succeeded among German moviegoers during the 1920s, since most of the films now lauded as classics were so maligned in their day. Amazingly, given its accessibility and continued fame nearly a century on, F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror falls into that sad category. It was the first effort by the newly-formed Prana-Film, one of the first "indies" that attempted to compete with the state-sponsored Universum Film AG, or UFA, which enjoyed a virtual monopoly in German film production. But an unexpected intervention by outside parties ensured that Prana-Film's first release would also be its last.

German-born Murnau himself came from a comfortable life, if harsh and disciplined by today's standards. Formally trained as an art historian, he abandoned an early painting career after realizing his efforts were, in his own words, "like Raphael without hands." His time spent as a reconnaissance pilot in the First World War and the death of a close friend altered him considerably, and Murnau, already fragile psychologically and physically, withdrew further into himself. His alienation was not helped by his hidden homosexuality; or, to be more precise, its legal interpretation as defined by Paragraph 175 of the penal code, Germany's infamous and long-standing law on "unnatural fornication" that equated homosexuality with bestiality. Although there was an increasing grass-roots call for 175's repeal from 1919-1929, there was a parallel movement for its expansion, which would ultimately come to fruition under the Nazis in 1935. Thus, much of Murnau's private life, compared to egocentric peers like Fritz Lang, remained shrouded in mystery for many years.

His first project, an anti-war film, never got off the ground due to the overall unwillingness from financial backers (the topic was not broached on German celluloid until its literature kicked the door in first.) Falling in with other artist friends with connections, his luck improved. Subsequent projects, including an early version of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde starring Conrad Veidt from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, are now sadly lost through a combination of bombs, neglect and nitrate. With 1921's Schloß Vogelöd (The Haunted Castle), some took notice of his knack for horror, and Prana-Film, formed by filmmakers with an affinity for the occult, approached Murnau with their idea.

Inspired by Hugo Steiner-Prag's illustrations for Gustav Meyrink's fantastical novel The Golem (1915), Nosferatu took its design aesthetic from an entirely different source than the cliched, 19th-century Victorian romanticism that so defined the vampire genre of the day. There was nothing suave, debonaire, or attractive about the ratlike vision put forth by Murnau and actor Max Schreck, a then-unknown that, due to his last name meaning "to frighten or terrify" in German, many believed to be a pseudonym for some more prominent actor who wished to remain anonymous. Unlike his peers, Murnau abandoned the elaborate studio sets and filmed on location in parts of Poland and Czechoslovakia, which was virtually unheard of in those days.

It is, of course, all the more ironic and satisfying that what became the quintessential vampire film in the history of cinema is the very one ordered destroyed by the Stoker estate. The film's producers naively believed that altering the storyline and changing names could circumvent rights claims by Stoker's widow. The courts didn't see it that way. At her request, all prints were to be recalled from distribution and destroyed immediately. One print leaked out to the international market and never made its way home; that was the oft-circulated legend anyway. As it turns out, prints surfaced piecemeal for decades and were slowly reconstructed to match Murnau's production notes, including tinting specifications--many "B&W" German silent films were intended to be screened this way--and mood preferences for the score.

Murnau emigrated to Hollywood and made Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, which was nominated for an Academy Award and still believed by many to be his greatest work, despite his disillusionment with the American system. In 1931, he died in a car accident in California, at the age of 42.

At this late stage, the massive gaps in Murnau's oeuvre will likely never be filled, with fewer and fewer lost films being discovered from the "archives" of broom closets and theater basements. But as a recent jackpot of "lost" John Ford films found in New Zealand shows us, film preservation can often take freakish and unexpected turns.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

______________________________________________________________________

Like Gray Gardens, Eat the Document, and Superstar: the Karen Carpenter Story, Mädchen in Uniform is one of those rare films whose only availability in the pre-Internet days came through the grainy bootleg copies that film buffs passed around hand to hand. The bad VHS copy I saw in college had the English subtitles partially truncated at the bottom, with Japanese subs taking up 1/3 of the right (couldn't get this copy for our screening purposes unfortunately.) Art transmitted through those types of personalized, underground channels always takes on some contraband aesthetic that inevitably influences ones interpretation of the work itself; so within the early-90s college film community, Mädchen in Uniform quickly became known as "that German lesbian movie banned by Nazis that they were watching in Henry & June." I believe this deep scholarly analysis should be expounded upon.

Examples of female directors from the Weimar years are almost non-existent. The first one often discussed is the technically-gifted, politically-clueless Leni Riefenstahl, an actor until 1932's The Blue Light, her directorial debut. She is of course better known for aggrandizing the Nazi rally at Nuremberg in her Triumph of the Will (1935) and was handpicked by Hitler to accompany the Wehrmacht into the invasion of Poland to get action footage for newsreels; the first "objective" embedded journalist I suppose.

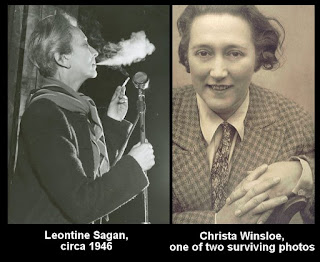

Luckily, for a little leftist balance, we have Leontine Sagan. Sagan started her career under Max Reinhardt's tutelage, acting and directing for the stage before turning her attention, albeit briefly, to filmmaking. Of the two feature films she directed, Mädchen in Uniform (1931) is her only surviving work, released just at the launch of German sound film; and while not as sonically groundbreaking as Fritz Lang's M, it nevertheless stands as a great achievement from that difficult transitional period and pushes boundaries in other areas.

Upon release, Mädchen in Uniform was a huge success in Germany and the most acclaimed film by a woman director to date. It also sold well in most countries that chose to import it, although an initial U.S. ban was purportedly only lifted after the direct intervention of Eleanor Roosevelt. Part of its German popularity surely stems from its being an adaptation from a novel, The Child Manuela by Christa Winsloe, which is based on her own boarding school experiences. While it remains unclear how Sagan was brought on board to direct, the film is one of those rare occasions where both director and screenwriter were women, as was virtually the entire cast. Since Sagan had zero experience in filmmaking, the experienced director Carl Froelich was brought on board to supervise the technical aspects and act as a "consultant." To this day his influence on the film is still a point of considerable debate among film historians, particularly with regard to how much pressure he exerted on the narrative. Feminist film theorists tend to undermine any positive contribution, or at least remain leery of his intentions, while actors like Hertha Thiele later sang his praises and offered belated insights into the onset dynamics between the cast, Sagan, Winsloe, and Froelich.

Looking back on the film's critical readings, one sees an interesting shift through the decades. In 1931, while the underlying homosexual overtones were noted and commented upon, this was not seen as a particularly important aspect of the story, at least with regard to media attention. Perhaps this had much to do with context, given the over-the-top sexual liberation of Weimar Berlin, where a suppressed love affair between headmaster and pupil would have been quite quaint compared to Marlene Dietrich's raunchy performance in The Blue Angel, the film that took the LGBT subculture in Berlin by storm, according to Hertha Thiele. Hence, until the 1960s, scholarship and critical reception focused almost exclusively on the film's indictment of Prussian militarism and its dehumanizing and destructive influence upon German society, which was by far a greater concern among the nation's cultural cognoscenti. Thiele says that this was also the narrative angle emphasized by Froelich, despite his later collaboration with the Nazi Party.

But times, and interpretations, change. And today, first and foremost, Mädchen in Uniform is seen as a landmark moment in lesbian filmmaking, not only because of its content, but also because of the team responsible for its creation, with the openly-lesbian Winsloe and somewhat-more-closeted Sagan overseeing all stages of the creative process. It was a fleeting moment not to be repeated by either of them. The following year, Sagan co-directed a watered-down male version for British audiences, Men of Tomorrow, an odd title given its retrograde ideals. She later moved to South Africa and directed for the stage for the next forty years. Winsloe's end is more tragic: near the end of World War II, she was murdered in a French forest for "associating" with a suspected collaborationist. The four Frenchmen who murdered them said that they thought the two women were Nazi spies; Winsloe, a staunch anti-fascist with Communist leanings, was anything but. All four were acquitted of any crime.

As for the actors, the success of the film resulted in the hugely-popular teaming of Hertha Thiele - Dorthea Wieck being joined again for Carl Froelich's Anna und Elisabeth (1933), where they again played lovers, albeit ultimately punished for their transgressions at the film's end. More notably, Thiele had a significant role in Bertolt Brecht's radically-progressive Kuhle Wampe, or Who Owns the World? (1932). Although the Nazis had already banned most of the films in which she starred, Goebbels approached Thiele with an offer to work for the Party's propaganda machine, to which she famously declared "I do not switch direction every time the wind blows," and shortly thereafter left for Switzerland, where she remained for many years, working in medicine.

When interviewed shortly before her death in 1984, Thiele said that she still received fan letters weekly, not from her then-current television work in West Germany, but from new generations of lesbians deeply affected by her anguished performance as Manuela from fifty years before.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

The fact that, after viewing Fritz Lang's M, one will never hear Grieg's Peer Gynt in quite the same way again speaks volumes of the film's most brilliant asset: its innovative use of sound. M is, without question, the high water mark of Weimar era cinema, and the best film of Lang's career in the eyes of many, including his own.

But let's back up a bit. Any meaningful discussion on the merits of M must be properly placed within the context of the coming of sound to the medium itself. Through the din of today's hyper-accessible, multi-media white noise, it is hard for many to comprehend silent film as anything beyond an inferior and defective medium that was only improved upon with the sonic innovations of the late 1920s, when the sound-stripping of celluloid finally synchronized aural with visual. But this is unfair; at the least a simplification, at the worst a gross injustice to the sophistication of the medium. By the coming of The Jazz Singer, silent film had evolved into its own complex film language, with its own rhythm, its own set of aesthetic rules; for example, by his masterwork Der Letze Mann, German director F.W. Murnau had managed to purge the ubiquitous intertitles altogether in favor of a universality of vision that transcended all languages and national demarcations. The artists' protectiveness of this evolution can be seen by the reaction to the proposed transition, particularly from the creative elements. Producers and studio heads saw the gimmick and the novelty, and the subsequent dollar signs. Actors and directors saw the destruction of their craft by technicians and artless "inventors" who capriciously hocked their wares to an industry that could not resist this shiny new toy. After all, this was no small change; it was jumping off a cliff so to speak. The film medium was still relatively new and on tenuous footing. One misstep and all could come crashing down. For Germany, France, and the other European nations struggling to get films exported abroad, the problems went far beyond microphone placement and minimizing set noise: the coming of sound can be seen as an early instance of American dominance via cultural hegemony, an attempt to assert control over the international entertainment market under the dubious guise of "innovation." At home, the new sound medium allowed studio heads the freedom to abolish existing star contracts and renegotiate on terms favorable to them, which they did with impunity, getting rid of a lot of squeaky wheels along the way. So no, it wasn't just about getting to hear Al Jolson sing.

So back to Lang . . . Okay, bare with this brief digression. In 1952, baritone-sax-great Gerry Mulligan moved to L.A. and started performing at the Haig with some other newcomers, including Chico Hamilton and Chet Baker. Red Norvo had just finished a tenure there and the upright piano had been removed from the stage to accommodate his older style of jazz. Mulligan--partly out of convenience, partly out of curiosity and the desire to push himself into uncharted territory--asked the management to leave it as is. As is evidenced in the earliest surviving demos, without the piano for harmony, this new quartet struggled with odd arrangements and awkward attempts at improvisation. But within weeks, their own unique song structures emerged, a West Coast jazz language built as much around communicative silences and pauses as East Coast bebop's was all about bombast, speed, and notes-per-second.

M is Lang's "pianoless quartet" moment, the point at which he struggled with a shifting technical variable--his first sound film--and ultimately envisioned something new, a use for audio beyond the banal conveyance of dialogue. He pioneered how sound could be manipulated to heighten the impact of constant intercutting between scenes, such as M's two concurrent discussions on how best to approach the capture of this troublesome child murderer, one happening at the police station, the other among the various "union" representatives of the criminal organizations, with Lang drawing ironic parallels between these two seemingly-opposed entities. In today's films, such a montage is standard and barely noticeable, even a tired cliche. But in M, it still somehow feels fresh and revolutionary. Similarly, his use of operatic leitmotiv to impress upon the viewer the disintegrating chaos of a killer's internal psyche is also highly advanced. And above all, the incredible intro sequence, with the girl's abduction told through the repetitive, increasingly-distressed, off-screen calls from her mother, stretched across a triage of haunting sequential images: a human silhouette on a "Wanted" poster; a child's rolling ball; a balloon snagged on a power line.

Lang's oft-repeated tale of fleeing to France in the "dead of the night" after being approached by the Nazis to direct propaganda films has always held more than a whiff of fish story, with its self-aggrandized danger and egocentric escapism, as if his notoriety and position would have had no impact on his fate. Perhaps that is true. But like Pabst, who also declined to serve, I suspect he would have been simply ignored and marginalized. Contrary to his version of events, he did flee with all of his money and resources intact and also made several return trips to Germany from Paris before the outbreak of war.

Although fellow ex-pats Douglas Sirk and Billy Wilder achieved a level of success in the US rivaling Lang's, it is only the latter whose cinematic greatness is divided equally between the pre and post war eras, with a cinematic canon spanning two languages. Lang would go on to direct some of the biggest and most important film noirs of the Hollywood era, particularly 1953's The Big Heat, starring Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame. In M, within Peter Lorre's complex serial killer, we see the early blueprint for what would become Lang's trademark motif, and a cornerstone of practically the entire film noir genre: the doppelganger in conflict, the intermarriage of good and evil, and the non-judgmental exposure of the "grey zone" between the two.

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College

James Bunnelle

Acquisitions & Collection Development Librarian

Lewis & Clark College